It’s not just technology that’s changed fast – the entire model of ‘effective engagement’ has also radically shifted. To stay as close as possible to the armed forces we serve, we at Thales must ‘think in loops’.

The last few decades have seen phenomenal advancements in military capabilities. Intelligence-gathering that could take weeks can be done in seconds. The precision of strategic missiles is now available in single munitions. Tech that once took a convoy to move is now on a tablet in a soldier’s pouch.

While we are familiar with how technology increases the range of options available to commanders and soldiers in their decisive moments, we are now poised to see an explosion in technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), Big Data analytics and massive digital integration that will change the very nature of the decision-making process itself.

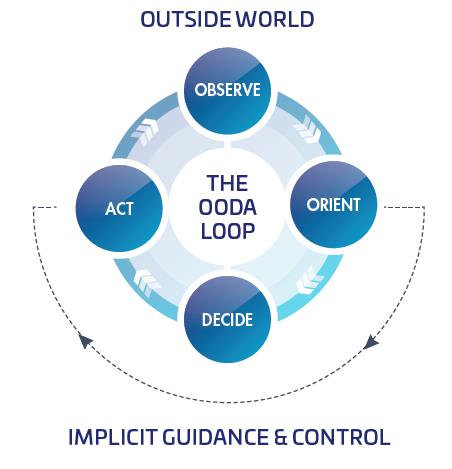

And if we at Thales are to use these technologies to full advantage, we must be very clear about how, why and where they fit within the military decision-making process. We need to know how technology fits with the OODA loop – the observe–orient–decide–act cycle.

What’s the OODA loop?

The OODA loop is a ‘competitive decision-making’ model formulated by American fighter pilot John Boyd. First created to help US fighter pilots gain the upper hand in dogfights, the OODA loop has been hugely influential in all military thinking. So far-reaching that Boyd has been called ‘the most influential man you’ve never heard of.’

From straight lines to loops

For centuries, military commanders practiced what the 4th century BCE Chinese General Sun Tzu called ‘manoeuvre warfare’, where victories were won by swiftness, fluidity, and surprise. But in modern warfare, while these elements often remained critical to success, there was no clear way to articulate how and why they were so important. In Vietnam, as Boyd saw numerous, better armed American fighters lose out to scrappier yet quicker Soviet MiGs, and on the ground, the world’s largest military superpower was beaten by the far less well-armed, but far more dynamic North Vietnamese, Boyd saw that speed of action and adaptation had been missing from the allies’ thinking – in everything from equipment design to strategy. The OODA loop, as he described it, is a way of restoring agile, dynamic responsiveness once again to the centre of Tier 1 military decision-making.

Going round the loop

Boyd’s insight was this: in combat – or any form of competitive activity in uncertain circumstances – we are always moving through four phases:

First we observe the conditions. Not just ‘seeing’, but actively absorbing the entire situation – ‘data gathering’ in the broadest sense.

Then, we orientate ourselves according to what we’ve learned – we’re synthesising information, and asking ourselves ‘given what we know, what options are available to us?’ This is the most important phase because everything is in play: our training, our experience, even our cultural expectations. And because good orientation ‘compounds’ – it affects all other phases: how we observe, decide and act.

Then from the options available to us, we decide what we should do, and then we act. By acting, we cause things to change, giving rise to new things to observe… and round the loop we go again.

In its simplest form, the OODA loop looks like this:

We go round the loop at all levels, whether long-term grand strategy responding to political changes, or individual soldiers responding to enemy fire. And at all levels, those who can move round the loop quicker than their opponent gain the initiative.

Added to that, those who can ‘get inside’ their opponent’s loop can disrupt their adversary’s decision-making and keep them in a state of confusion, reaction and panic.

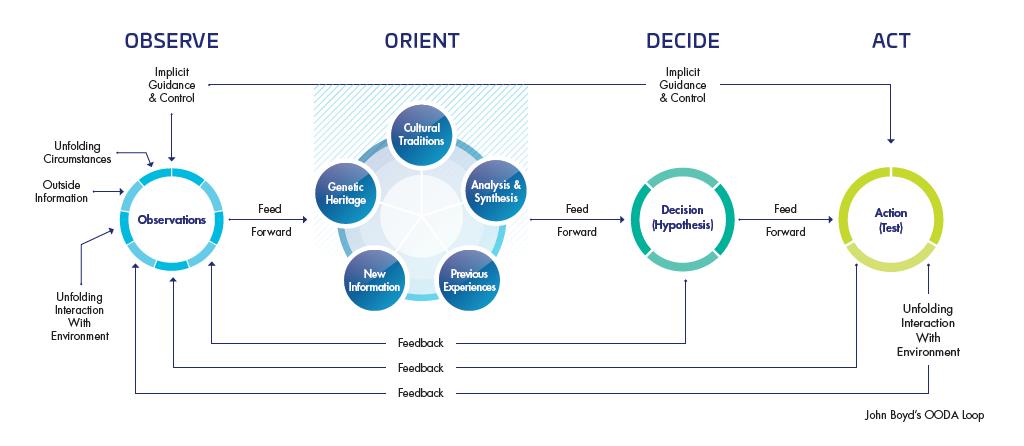

In combat, and in life, of course, things aren’t quite that simple. At each stage, we create dynamic feedback loops that interact with each other. That’s why Boyd’s complete diagram of the OODA loop looks more like this:

For us at Thales the importance is clear – to understand where the application of technology has the greatest effect on ‘increasing the tempo’ of the loop, and so create the greatest advantage for commanders and soldiers. They then know they can rely on our connected capabilities to observe, orientate, decide and act according to their ambitions. This application of our key trusted technologies provides militaries with decisive advantage.

Getting super at OODA

Boyd was also clear that the OODA loop was not a merely mechanistic process – and that those who ‘OODA’d well’ had certain creative, as well as ‘moral and mental’ traits in common such as embracing the chaos and working with mutual trust, intuition and focus:

Embracing the chaos. It’s easy to think of the OODA loop as a ‘decision-making model’ – something that helps us ‘control’ external forces. It’s not. Boyd saw that combat – indeed, all of life – is always uncertain and ambiguous. Those who thrive are those who embrace uncertainty as opportunity, who revel in fluid and ever-changing situations.

Working with mutual trust, intuition and focus. Boyd also saw that groups who trusted each other, who were able to operate by ‘feeling’ as much as rational deliberation, and who could keep the ‘big picture’ in mind without needing micro-managing (what British forces would call ‘mission command’) were best placed to OODA most effectively. They were more confident in trying different things in the ‘orientate’ phase, and were frequently able to skip an explicit ‘decide’ phase.

It’s the decisions that count

Looking at decision-making through the lens of the OODA loop also highlights one of the huge opportunities – as well as one of the biggest challenges – of emerging technologies such as AI, Big Data analytics and digital integration: gaining ‘OODA advantage’ through being ‘comfortable with uncertainty and chaos’ is psychologically extremely difficult for humans. But computers don’t even notice. ‘Can you keep your head while all about are losing theirs?’ For an AI, the answer is a resounding yes.

However, we can also see that these technologies will only be effective in OODA loop if the human decision-makers trust them implicitly – trust their reliability, the veracity of their data, and the quality of the decision options they offer. This can only come about through the highest levels of integrity and cyber security – something which Thales understands implicitly and has years of expertise in.

Applying ‘OODA thinking’ helps us at Thales stay clear on the benefits of applying emerging technologies– by constantly evaluating their ability to 'increase the tempo' across the whole loop and contribute to achieving advantage – for the soldier, commander and decision-maker of the future. We believe in the augmentation and amplification of what soldiers do, not just a reliance on technology. People on the battlefield need key technology enablers. And that is what we provide to modern forces every single day.

Because, to paraphrase Boyd: it’s decisions, not weapons or doctrines, that win wars.